About the author: David Quan, one of thirty recipients worldwide of a Cambridge Trust Scholarship, was one of our state’s top performing students, earning a near-perfect ATAR and International Baccalaureate (IB) score. An Order of Australia Association Student Citizenship Awards recipient, David has tutored, coached and mentored hundreds of Primary and Secondary students over the last half-decade, especially through his active volunteering and leadership roles for school, basketball, music, public speaking, social enterprise and community service.

Advanced Education SA is pleased to partner with David before he commences his undergraduate studies at the world-renowned University of Cambridge. We hope that his fresh insights and perspective may offer all our students further inspiration to access excellence and advance their education. For private and group tuition enquiries, please visit our website at https://advancededucation.com.au/

Note: Original Article HERE

Think back please to your good old days. When was it? What made it so good?

Good Old Days or Not So Good Old Days?

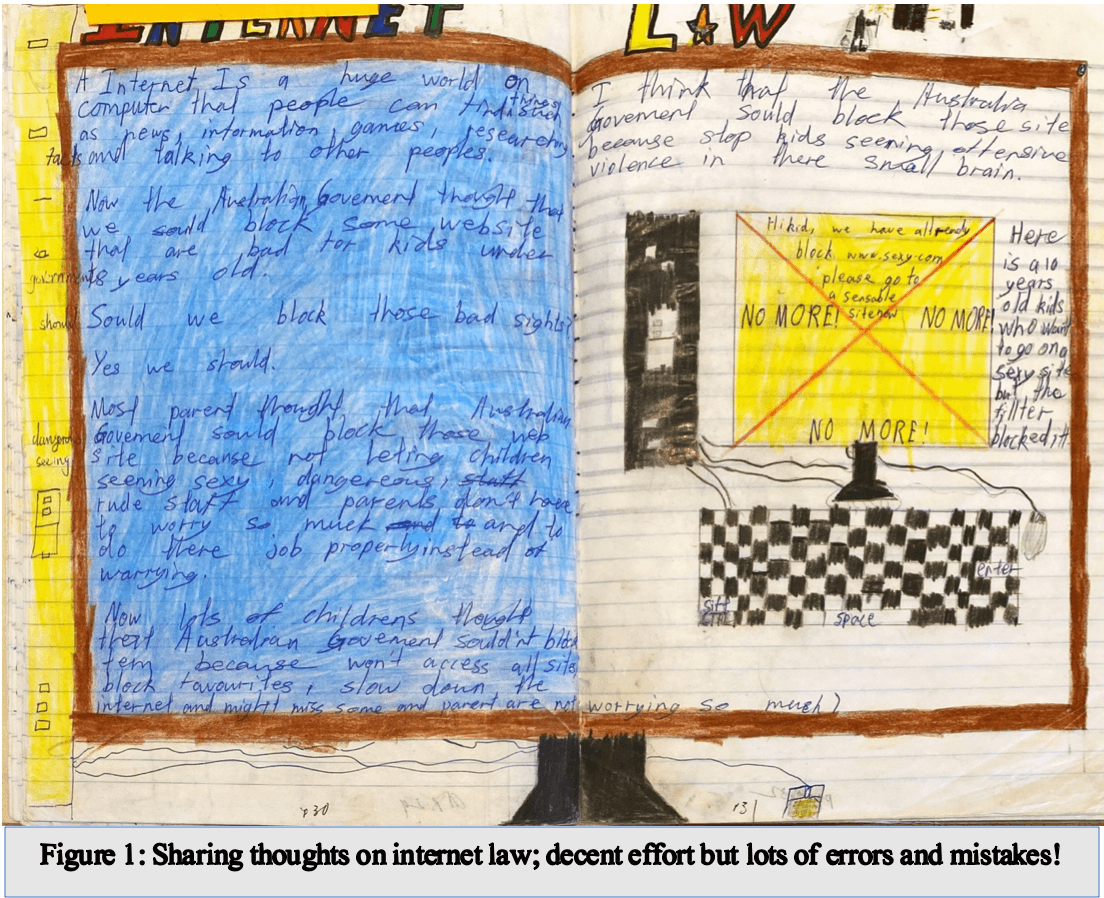

Year 4 would’ve undoubtedly been my good old days. The learning that year – specifically, as a report writer – was most significant. I took absolute pride in the work: one report, for instance, was produced after working almost every day on what was supposedly a 3-week holiday. It was a big deal! Needless to say, the ideas were well-explored; the spelling, grammar and punctuation were near-perfect – at least, for an Upper-Primary School level.

I truly believed in my abilities until a few years ago when I decided to re-read those presentations. Whilst I had expected to detect some elements of childishness or messiness of handwriting, I wasn’t prepared for the countless previously unnoticed spelling, grammar, and punctuation mistakes. That caused an older-me to scowl and lose patience in frustration. God knows what I would have thought of a Year 4 if he or she would make those mistakes. So, it made me wonder: What had caused this disparity between my memory and reality? To not realize those seemingly inexcusable and, frankly, dumb errors just seemed incomprehensible and careless.

A True Moral Exemplar: Mr Gerry McCarthy

But there’s more to this: contemplating the conundrum led me to reflect on the influence of Mr Gerry McCarthy, my Year 4 teacher. Seeking to understand his approaches changed my behaviour, outlook, and attitude, in a palpable manner. So, buckle up and allow me to present the genius of Mr McCarthy – a man who I consider to be a true moral exemplar. I’ll do so, to the best of my ability, with appropriate grammar, punctuation, subheadings, visual features, and captions – all elements that he advocated for an effective presentation.

1. Modelling Open-mindedness

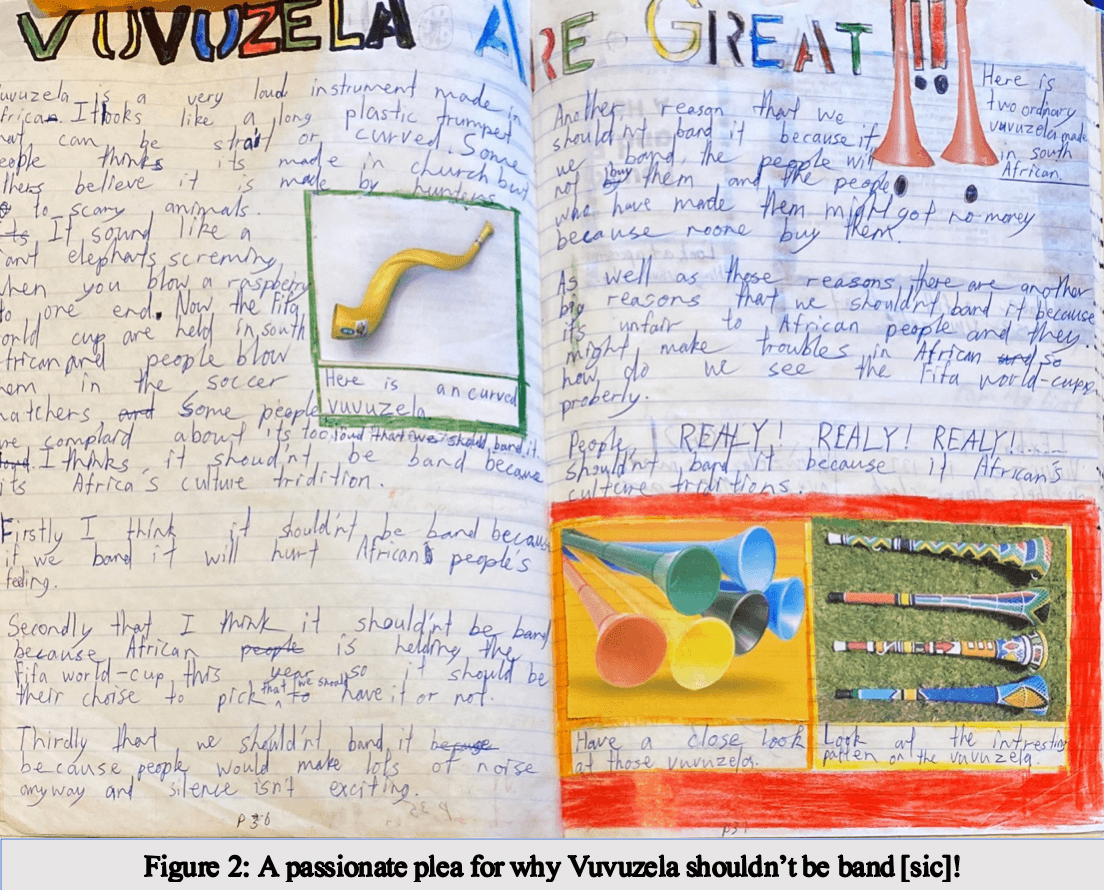

Our weekly class routine was to watch Behind the News (BTN); Mr McCarthy consistently challenged us 10-year-olds with “Why” questions. Why public and private hospitals? Why keep Vuvuzelas for the 2010 FIFA World Cup? Why?

What mattered was his modelling of open-mindedness, attentively listening to each of our responses. Though he often argued and questioned our reasoning, he rarely discounted our opinions. When the teacher – in our eyes, the most respected and knowledgeable person – ‘argued like he was right, and listened like he was wrong’, we noticed and reciprocated. This not only created a safe sharing environment, but also indirectly suggested that issues can be nuanced. We therefore subconsciously practiced critical thinking and learnt the need to consider multiple perspectives!

2. Valuing Creativity

After listening to others, we were encouraged to present our personal viewpoint in the form of an exposition, report or discussion, for which we were assessed on three broad categories: Presentation, Content, and Language. On the one hand, this threefold marking approach emphasised how considerations of the audience may be just as important as the content itself. On the other hand, this enabled creativity and self-exploration. There were no scripts, no inflexible rules, no Mr McCarthy looking microscopically at everything we did. Thank goodness! To him, students must have been similar to jazz musicians: they are at their best when they use the notes on the page merely as inspiration to improvise for specific audiences. Valuing creativity, without an over reliance on rules, was Mr McCarthy’s gift to empower.

3. Appealing to Virtue and Service

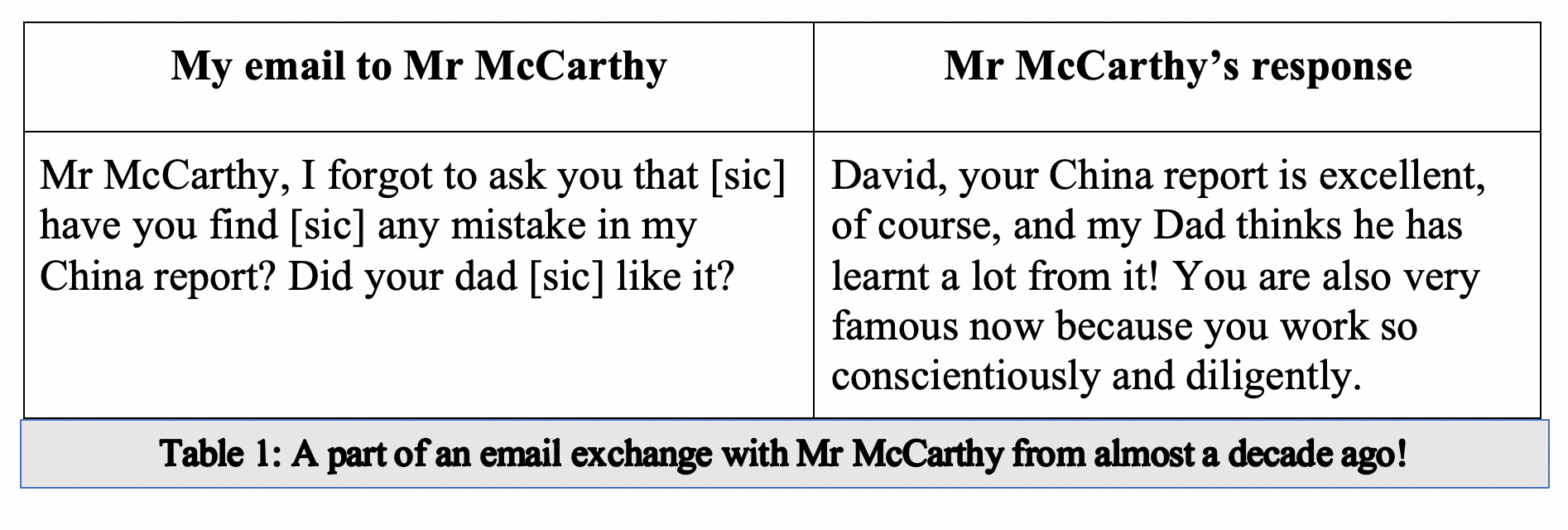

Decent grades or ‘not unhappy’ parents are common incentives teachers use to motivate students. Not Mr McCarthy though! How then did he effectively motivate? This email exchange almost a decade ago is perhaps most revealing:

That “China Report” was a 7 A3-paged Terracotta Warriors presentation – a self-directed month-long project motivated by a desire not only to learn, but also to delight Mr McCarthy’s father – evident by the email exchange. I’d never met Mr McCarthy’s father, but herein lies the secret: Mr McCarthy understood that we all wished to contribute to something far greater than ourselves. We all want to do the right thing in the right way for the right reasons.

In fact, don’t we all want to feel like somebody else’s life is better because of us? Fear and authority instill compliance and mediocrity, but struggle to inspire intrinsic motivation and excellence. Hearing about his father’s interest in the Chinese culture was unsurprisingly the best stimulus for me.

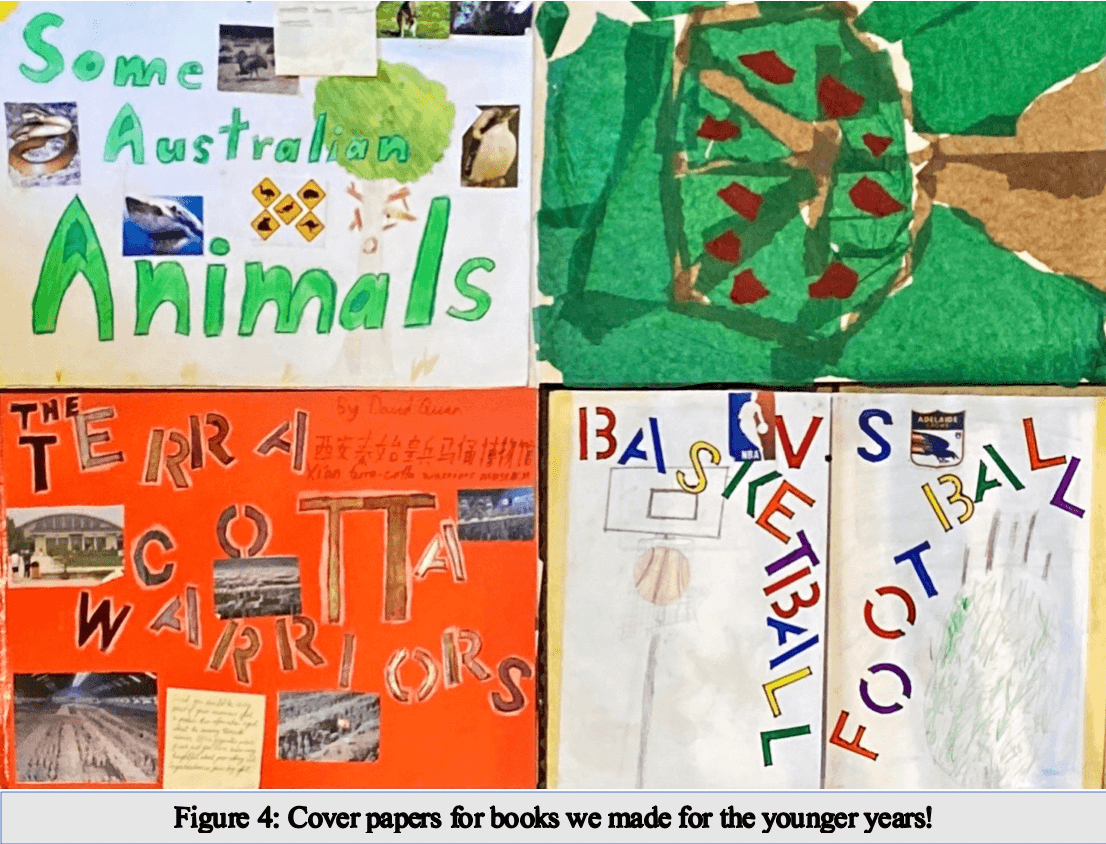

Mr McCarthy encouraged us not to merely approach our reports as school assignments. Rather, we could view them as important presentations that, if done well, could help to enlighten, entertain, or educate other people. Even as kids, learning became self-driven when it was aligned with our innate desire to make a difference. Many of us even opted to create ‘books’ in our free time after Mr McCarthy suggested that those could be borrowed by the younger years. Appealing to virtue – allowing us to align our personal learning to satisfy our innate desire to serve – was the most effective motivator.

4. Focusing on Language and Effort

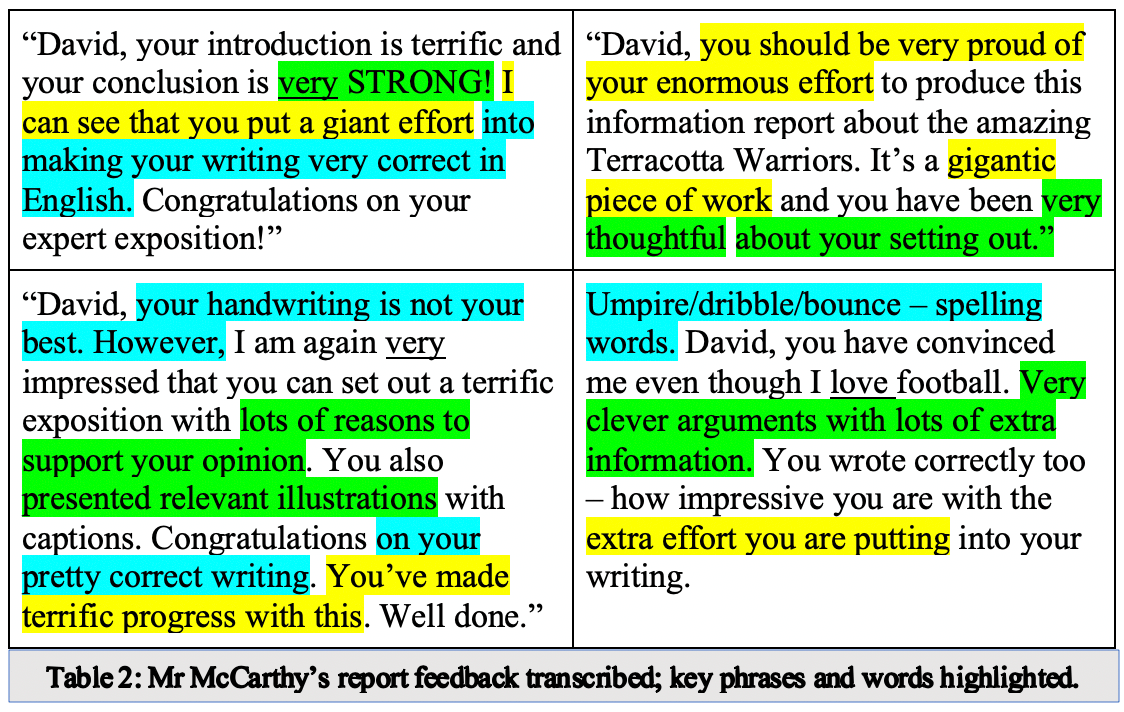

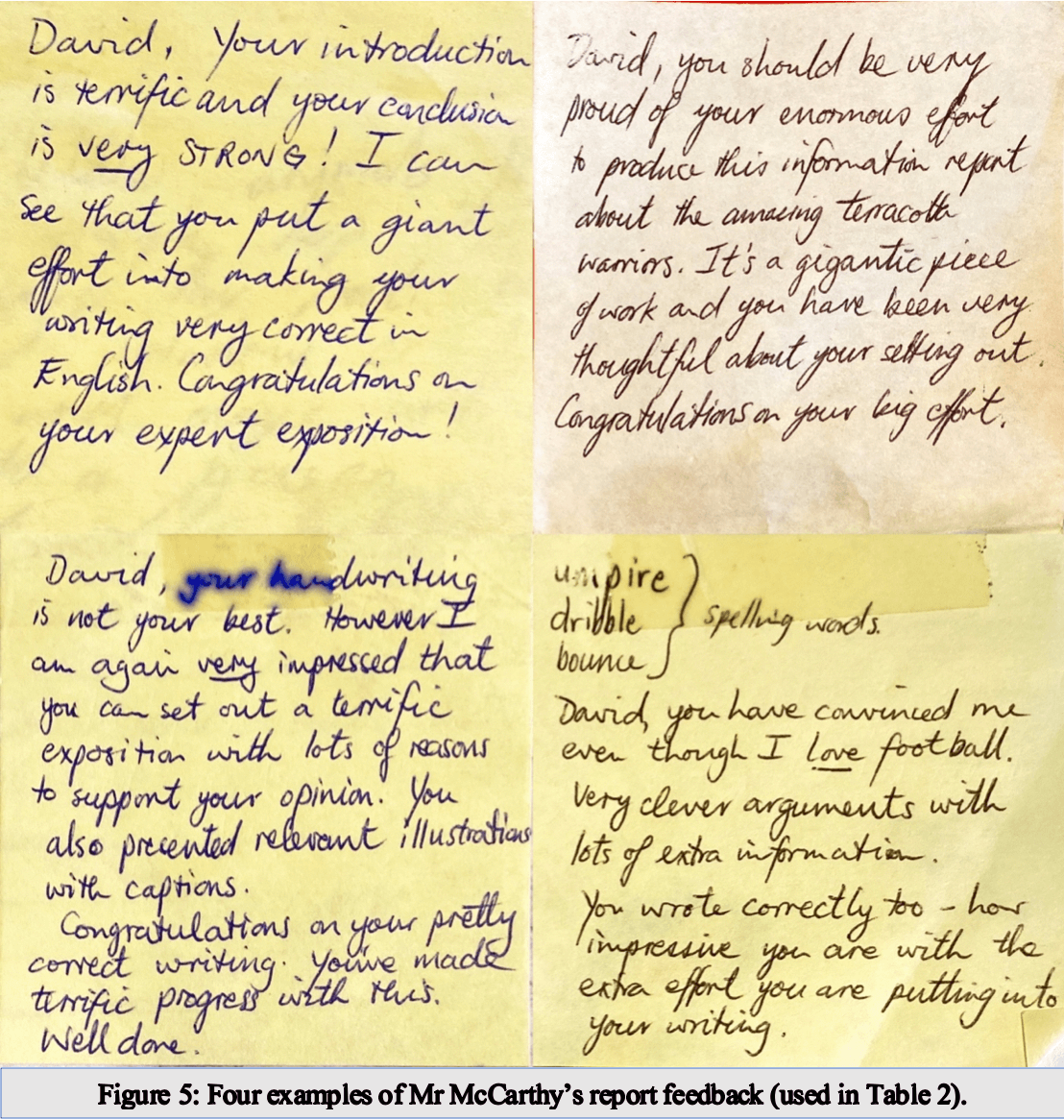

As mentioned before, my writing in English was far from superb – even for a Year 4. But there was a common thread with Mr McCarthy’s written feedback. Let’s use the photo below as four examples to illustrate his genius. In particular, take note of the highlighted phrases.

GREEN serves to emphasise creativity, thoughtfulness or judgement. Mr McCarthy modelled his open-mindedness by recognizing students’ individualised and creative approaches.

YELLOW concerns effort or progress, something Mr McCarthy prioritized. He understood the subtle implications of language; specifically, how praising talent – “You’re a natural!” – is different to praising effort – “You’re a learner!”. Whereas the former insinuates that learning and achievement are dependent on one’s genes or environment (fixed-minded), the latter suggests that our daily choices, or how hard and smart we work, can lead to further improvements (growth-minded).

BLUE offers feedback. To ensure clarity and eliminate misunderstanding, Mr McCarthy mostly delivered feedback in person. But in the rare cases that he included them in writing, his feedback was almost always connected with YELLOW, implying that effort could lead to improvement. That connection and simplicity offered hope.

These examples show how Mr McCarthy focused far more on input than output. My writing was not actually brilliant, of course, especially if judged by adult standards. What if he had discounted the effort due to all the mistakes and shortcomings? What if he had rigidly followed rules, and thereby not encouraged questioning and creativity? What if he had ruled with his authority and motivated through fear? All of these may have been easier choices to make.

Perhaps there wouldn’t have been that disparity between my memory and reality. I would’ve known just how terrible I really was! But I wonder whether that would’ve been effective and productive, or achieve just the opposite: stunting learning, dis-incentivizing effort, or disheartening the confidence to contribute. Mr McCarthy modelled the belief that persistent effort would lead to long-term improvement. His adaptation, in accordance to a standard most appropriate for each individual, showed wisdom.

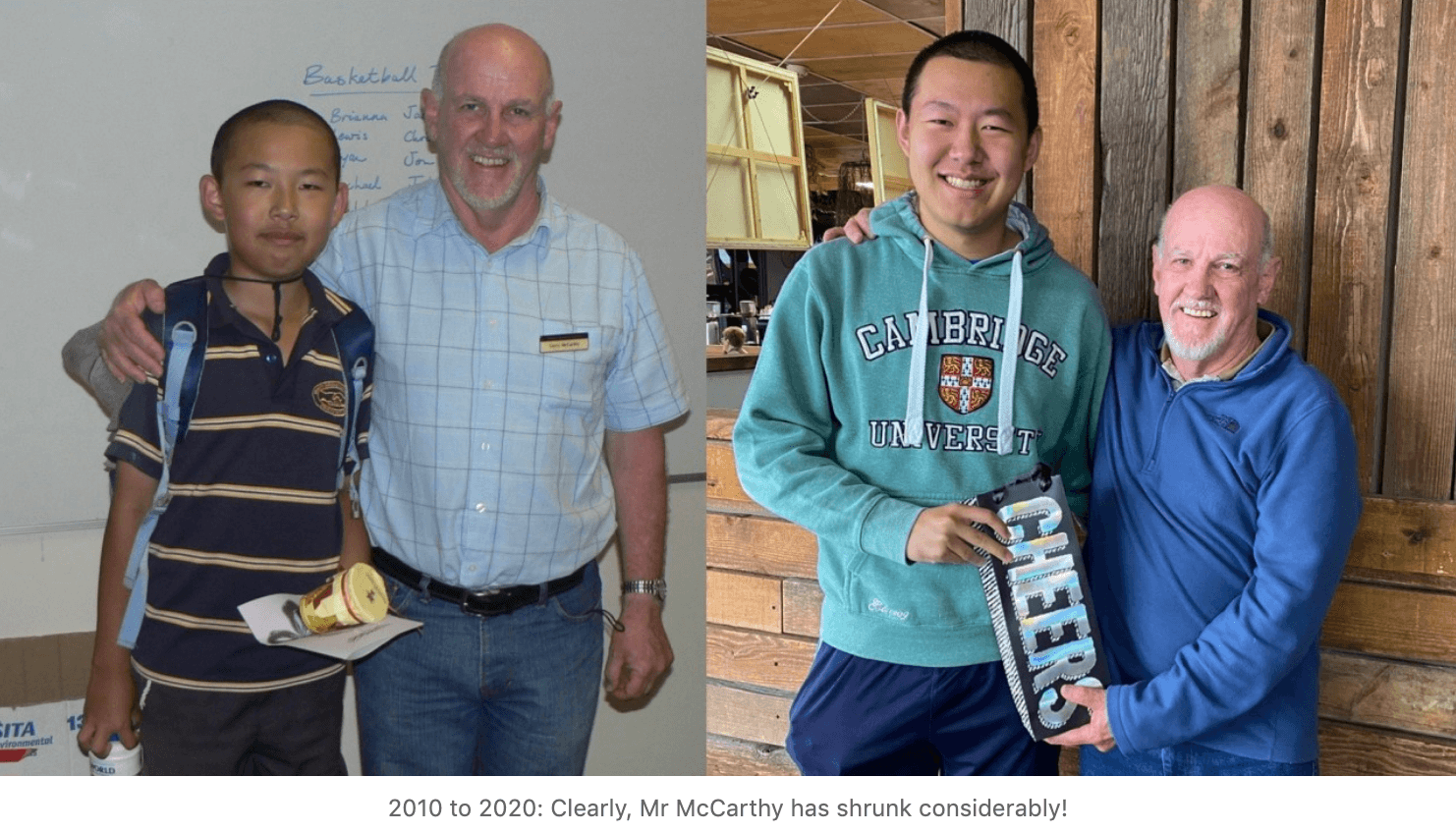

One Decade Later: 2010 to 2020

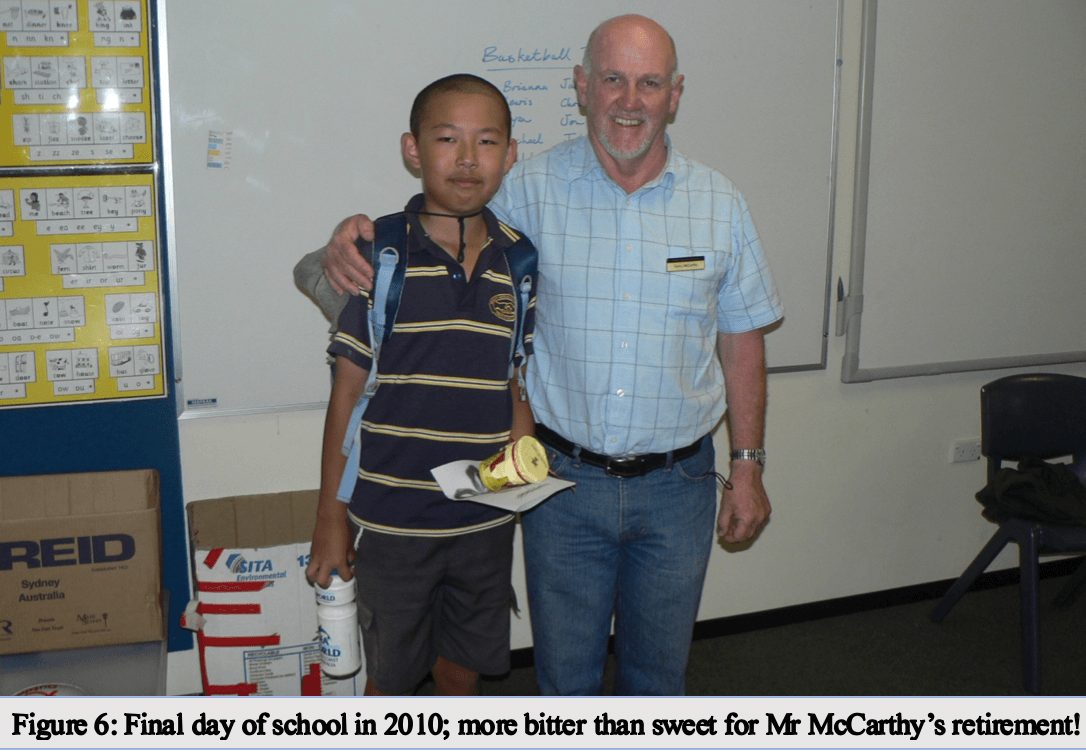

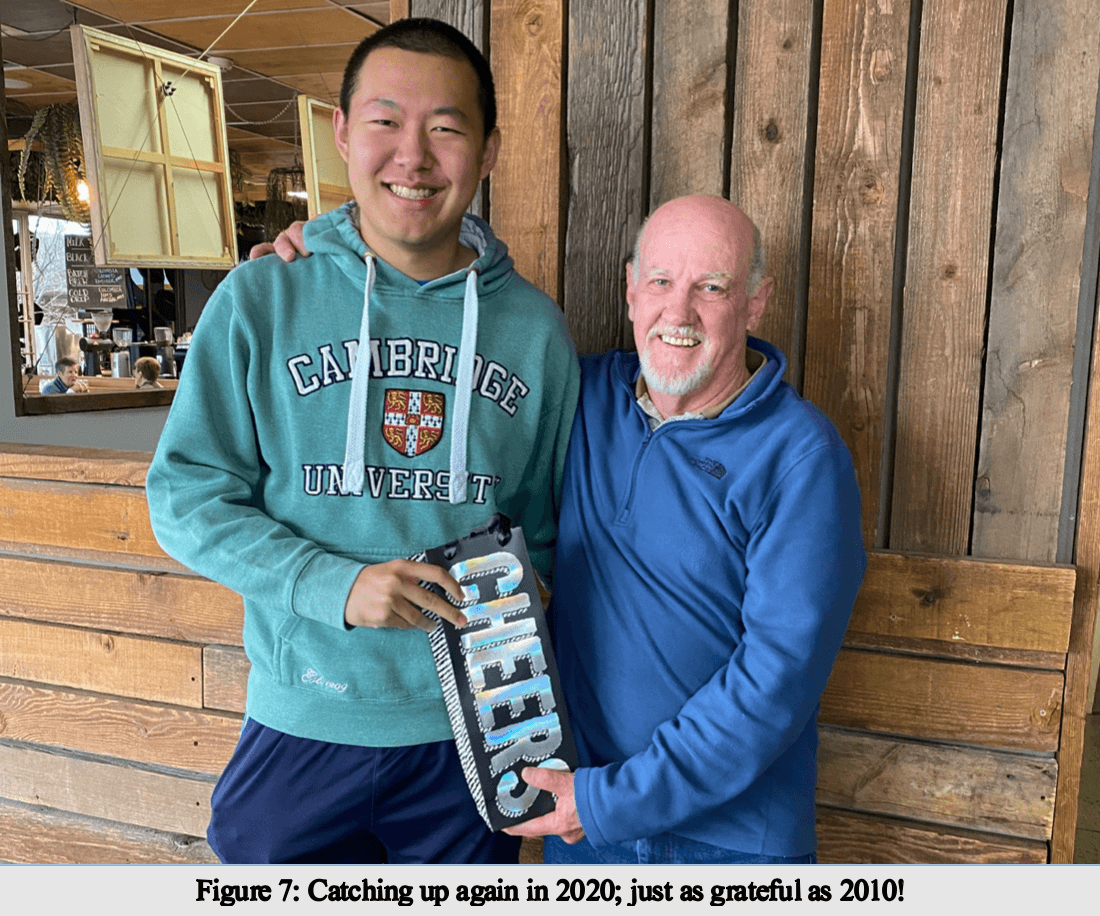

For these considerations, I always felt enormously indebted to the man who led my Year 4 class. So, when the social restrictions eased, we arranged to catch up again – to share some time together, to discuss, to express gratitude, and to relive the good old days!

One decade later, what I observed in Mr McCarthy was just what I had expected: a wise and humble man who genuinely listens, models open-mindedness, shares a sense of humour, values creativity, and regularly volunteers. What impressed me was his clear and accurate memories from even a decade ago; for example, how Ryan conquered his initial nervousness for public speaking or why Dominique admirably persevered with maths using base ten blocks. Personally, he remembered my lack of ability, though he concentrated his reflections more on my eagerness to learn. Those moments of trying, he argued, best shaped and developed character. Mr McCarthy remembers even a decade later because he still cares.

Mr McCarthy’s Concluding Wisdom: Remember Our Roots

You may argue, of course, that much of what Mr McCarthy demonstrated is a recipe for disaster in the so-called ‘real world’ – too unrealistic and idealistic. There are definitely valid reasons for toughness and forthrightness. I acknowledge too the necessary focus on outcome and results that drives companies and corporations. Mistakes, errors, and shortcomings may also bring tangible consequences, of course. Fair enough, I get that: it’s most wise to hire or promote those who are ‘ready’ – who can deliver right away. But I argue that more often than not we – especially me – can still benefit from being more empathetic and open-minded.

Here’s something to consider: the final important lesson Mr McCarthy emphasized was the value of remembering our roots. He attributed his early struggles at school, in fact, to be most influential in the nurturing of his considerate teaching and personality. Over time, we accumulate experiences, adapt to our circumstances, and evolve our identities – so much so that we may hardly remember our immature former selves. Yet if we take a moment to be objective – to remember our roots – we may realize how unreasonable it is to hold those who are more inexperienced than us to our developed and polished standards. Equally, isn’t it foolish to impose limits or restrictions on any younger person’s future, when people can learn, grow, and transform? We only need to look back to see where we were one decade ago. This potential to change our lives through small decisions over time is what makes us human. In fact, it’s this very possibility and unpredictability that make life worth living, right?

Let’s Start by Celebrating Our Moral Exemplars

So, let’s be kind to others. Let’s support those who give things a go by acknowledging the transformative potential of learning. Let’s be patient with those who ask us questions by recalling our humble journeys. Let’s specifically reflect on those moments of immaturity, inexperience, struggle, naivety, embarrassment, and failure that would have characterised our developments, shaped our decisions, and enabled our current achievements.

Let’s also remember those who once influenced, encouraged, or supported us. Most importantly, make it our habit to pay that kindness forward. This starts with us noticing, appreciating, and acknowledging our moral exemplars – those anonymous extraordinaries like Mr McCarthy who humbly serves, enriches, and empowers our communities with indispensable kindness, compassion, and wisdom. Seriously, let us celebrate them!

In 2030, I’ll almost certainly look back to 2020 in a similar way as I now look back to 2010: in utter disbelief at how naïve I once was in the good old days!

But at least God knows – as Mr McCarthy would too – that I’ve tried my best.